I wish that I could’ve seen the thing from slightly outside of myself. I realized when it was over that there were two processes happening: the discourse and interactions in the workshop itself, and the workshop in dialogue with the our design process and the goals of NIIP as a whole. As the day went on, I think I lost myself in the immediate; wanting to skip ahead to design “solutions” feeling helpless towards the communications barrier between experts who were approaching this problem with an array of very different tools.

Taking another walk through the series of forested pockets in the high marsh helped get some perspective back. Then, talking to the team, I could recontextualize and position myself in the future of this sandbar. I realized that what we really came away with was a comprehensive understanding of what’s possible; specific knowledge about the locality itself and the entanglements of stakeholders, tools, and shifting and accreting ground and ocean floor.

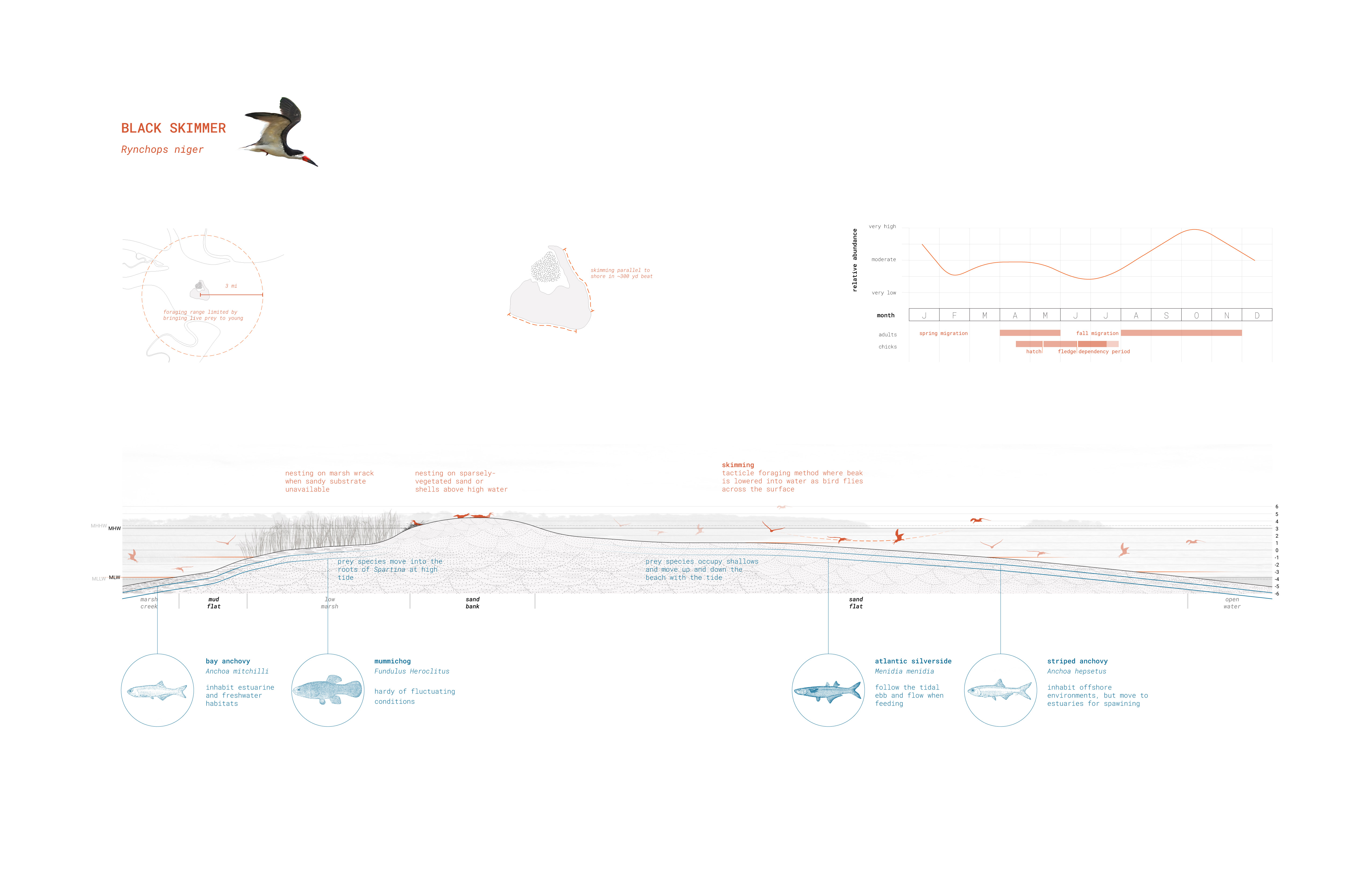

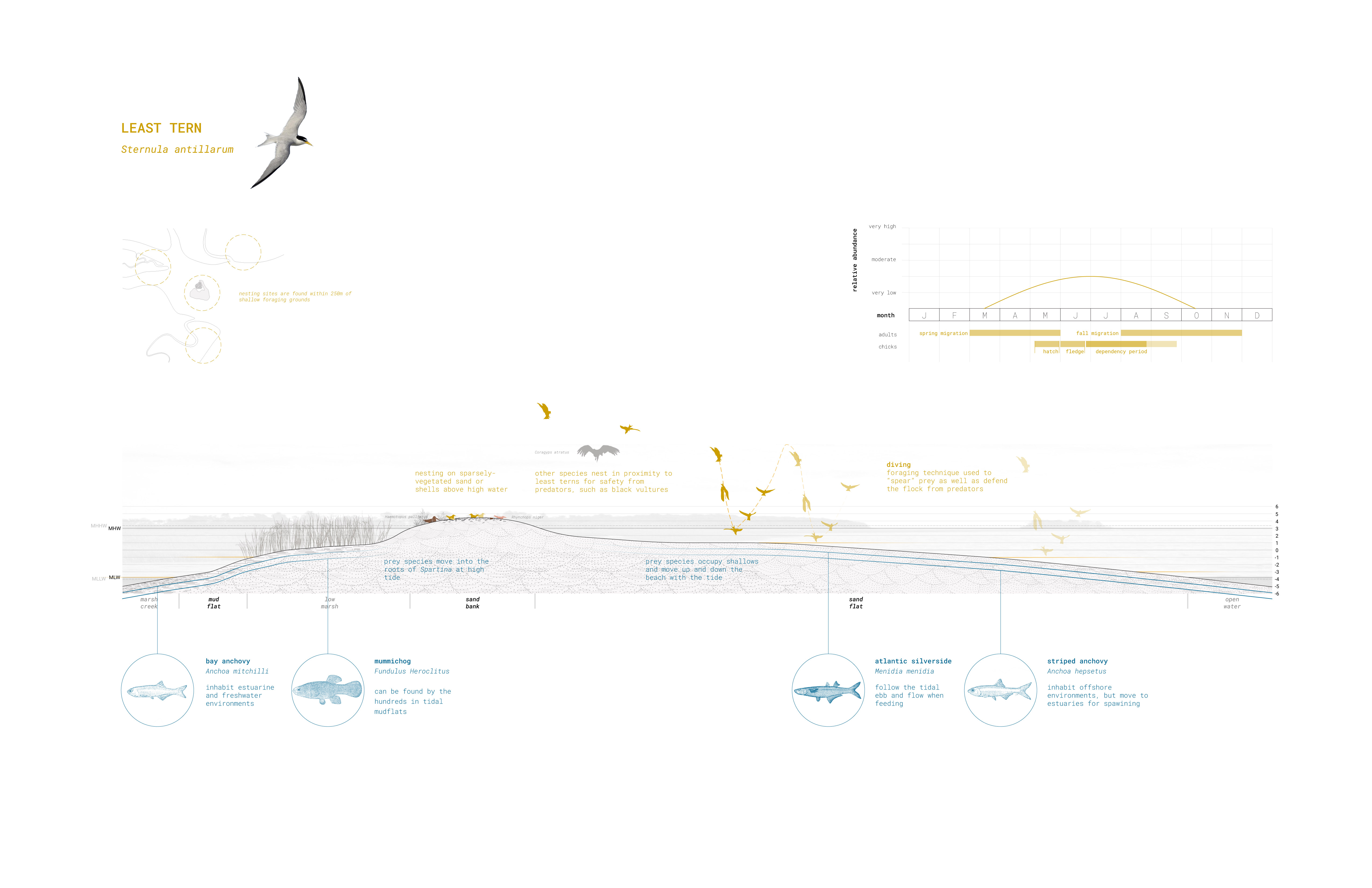

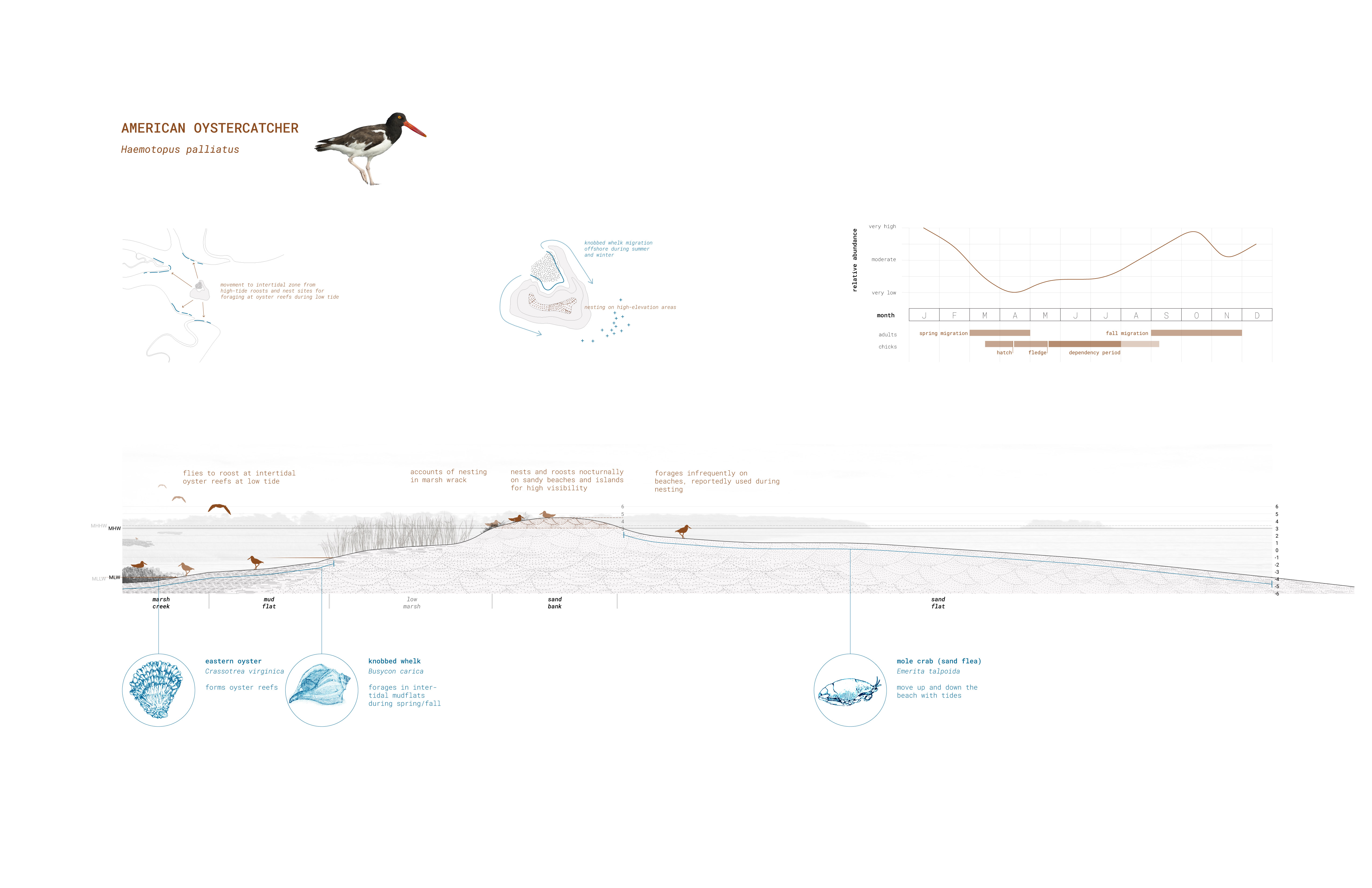

Upon further reflection today, I think what challenged me the most was learning exactly how much this site matters. It matters a great deal. Certainly to those who visit it and manage it, as well as to thousands of shorebird, horseshoe crabs, and other fauna and flora whose existence is dependent on this fluctuating sandbar that barely breaches the MHW line.

This anxiety is something that has bothered me since I began thinking about ecological landscape design at Beebe Lake. What if this is not mine to change? What if it is better untouched? Who am I to believe that my touch can be better than that of nature?

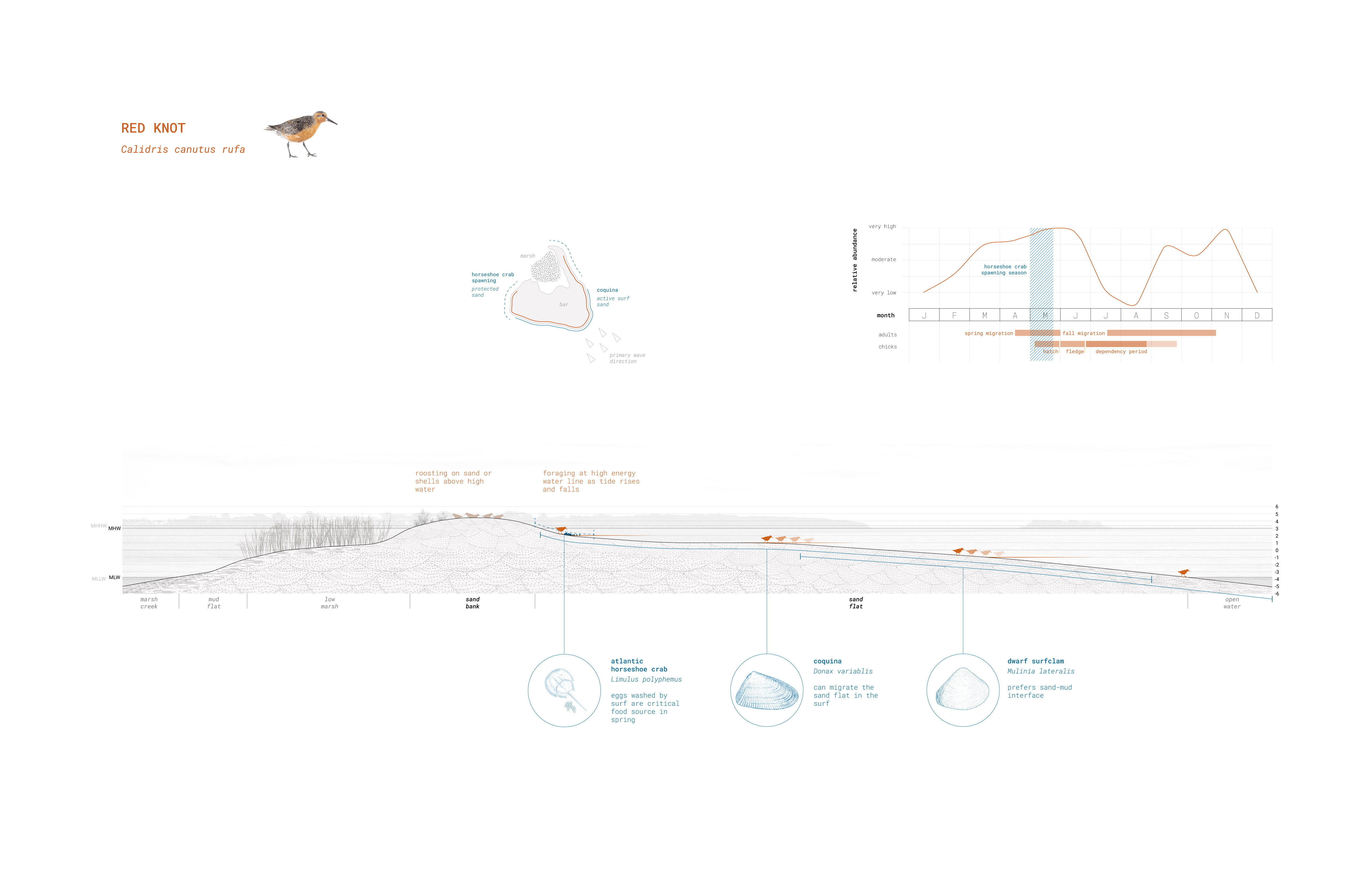

This fear of liability and proclivity to stasis is the problem. Yes, alterations to Ogeechee Bar could create more horseshoe crab habitat and reduce the density of crabs in the spring whose repeated burrowing action on these specific intertidal shoals and is intense enough to unearth previously buried eggs that are caught by the tide and provide a critical spring food source for migratory birds like the Red Knot. Yes, creating new bird habitat could act as a sink, rendering birds vulnerable to depredation and human disturbance. Yes, placement of fine sediment on the submerged fan could cause additional marsh accretion the the western portion of the bar, allowing predators to access the nesting site. Yes, everything could go wrong.

But what if we do nothing? Thousands of nests are regularly destroyed by high tides and human disturbance annually. Marsh is accreting on the western part of the bar and it is probable that it will continue to do so. Sea level rise will conceivably eliminate this habitat permanently in the long term, as higher-frequency storm events and high tides continually wipe out the supratidal portion of the bar and overwash nests. And sediment that could conceivably be used to elevate the site is clogging navigation channels or being effectively removed from the systems and relocated to upland and offshore dumping sites.

To expand on a conversation had at a picnic table with the team and some USACE engineers: any net positive change is greater than no change, successful regardless of any idealized goals. In the short term, doing nothing will feel better. But in the long term, doing nothing is the only choice that assures failure.

If we can get ahead of this wicked problem by implementing optimistic, considerate, and adaptable test-solutions, we will be successful. The process starts with small tests of our own.